Why did I choose the Street Retreat in Boston, instead of Los Angeles, New York or San Francisco? One reason is the weather. I prefer heat over cold, and August in Boston matches my constitution better than Los Angeles in April or December in San Francisco. My decision to go to Boston was also influenced by Rough Sleepers, a book written by Tracy Kidder about a doctor named Jim O’Connell who has devoted his career to healing the homeless, particularly in Boston. It’s a fascinating, illuminating, heartbreaking and hopeful story.

A summary from Tracy’s website is as follows:

Nearly forty years ago, after Jim O’Connell graduated from Harvard Medical School and was nearing the end of his residency at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Chief of Medicine made a proposal: would Jim defer a prestigious fellowship and spend a year as a doctor to homeless citizens? Jim took the job because he felt he couldn’t refuse. But that year turned into his life’s calling—to serve the city’s unhoused population, especially the ‘rough sleepers,’ people who sleep on the streets, in the rough.

Dr. O’Connell’s initiation into caring for homeless individuals did not involve diagnosing or prescribing. He built rapport with them by washing their feet. And then, as they gradually began to trust him and share their stories, he listened. As a spiritual director, I resonate deeply with his approach. To be truly heard is to be seen and appreciated for exactly who we are, no strings attached. We discover that although we make choices that in retrospect seem wrong, there is nothing inherently wrong with us. And that is a path to healing.

The prospect of crossing paths with this inspiring man and witnessing the infrastructure in place as a result of his efforts drew me to Boston.

And now, for the first time in my life, I’m getting a glimpse into the lifestyle of a rough sleeper. Our first night of sleeping on the streets, out in the open, bathed in city lights and city sounds, is definitely rough.

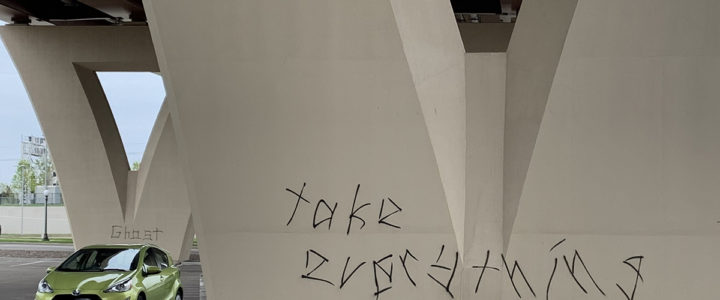

We ask a sturdy, bearded man pushing a shopping cart where on the street is a good place to sleep. He says all around the central library, which is where we are, having finished our ad hoc meal. A few of us scope out another side of the library. It’s quieter, much more peaceful than Boylston Street. However, just as we begin to claim a space large enough for the eight of us, an elderly couple arrives. “This is our space,” the man says firmly. Our credo is to not take anyone’s space, whether inside a shelter or on the street. We cede the territory and return to the front of the library and arrange cardboard and blankets in the space along the large library windows.

Laying on my back, a floppy hat over my face to block some of the light, I wonder how in the world I’ll be able to fall asleep. Clusters of people between us and the street laugh and bellow. It’s a party we’re probably crashing. One group putters with a banged up moped, trying to get it started. A noxious odor finds its way to me: spilled gasoline? The engine starts with a roar and after a long 30 seconds the moped leaves, stuttering. Meanwhile another group is doing and dealing drugs. One of the individuals enters our space and speaks to Joshin: “Is this some kind of social experiment?” He’s satisfied with Joshin’s answer for a bit, then returns for more. I witness this through grommet holes in my hat.

I close my eyes and consider the strong possibility that sleep will not come easily tonight.

At one point the tenor of the party shifts. Voices sound tense, angry. I pull off my hat and see four men intertwined, pushing and shoving, coming perilously close to our lineup of bodies prone on the sidewalk. A drug deal gone bad. Joshin motions to get up. I nudge the other Wendy who is laying beside me, tell her we have to go. NOW. Each of us quickly gathers our belongings as the men continue to yell and shove. “Leave the cardboard!” Joshin says. Then only Peter is left in the space, slowly gathering up his belongings, and Joshin urges him to hurry. One of the angry men walks up to Peter and gets in his face. Another man interferes, for some reason protecting Peter, a gentle neurologist nearing retirement.

With no time to stuff our blankets and belongings into bags or backpacks, we gather them loosely in our arms and walk across the street and down the block to an area that’s quieter, more residential. A small plaza in front of a yoga studio looks inviting. John, a muscular Canadian and veteran of Street Retreats, and the other Wendy and I scout the alley for cardboard. It’s easy to find in the city. Sometimes there are stacks of flattened boxes placed in the alley, presumably for the recycler. When we return with our found padding, the group organically positions cardboard and bedding in an L shape along a brick wall and the storefront. Then we settle in, hoping for sleep.

While on my back, the paper padding beneath me seems relatively comfortable. The problem is that I’m unable to fall asleep on my back. My body relaxes enough for sleep only I’ve arranged myself in a fetal position. I roll over, facing the bulk of John who is laying less than two feet from me. To my left is the corner of the L. Sandwiched among my companions I’m reminded of the peacefulness and joy of my youth during slumber parties – waking in the middle of the night, hearing light snores rise from still mounds arranged haphazardly across the living room floor. At this moment, sleeping on a street in downtown Boston, I feel connected to my companions. To the earth. And to God. I am not alone.

I’m awakened by two voices yelling at each other. A female and a male, volleying complaints back and forth. The only words I can distinguish are f*** and f***in’, which seem to be major building blocks in the woman’s vocabulary. I’m amused by a thick Boston accent. The heated argument continues for many minutes, then suddenly ends as if doused. I roll over, giving the right side of my body a break from the crush against concrete. There’s not enough padding in my body to cushion my hip bone or shoulder. I see that Helena, a young woman from Canada, is sitting up. She motions to me in a sign language I somehow understand as “I need to pee.” Our group’s pact is that no one leaves the group alone. We return to the alley where I’d scrounged for cardboard. First she pees behind a large dumpster. Then I take a turn – might as well, as long as I’m here. A car pulls into the alley just as I begin to stream urine. Although I’m hidden, I feel a sense of urgency, not from my bladder but from my mind as it imagines the worst. The car slowly rolls past Helena and me as we return to our street beds.

Somehow I fall back asleep in the relative silence that has returned to the neighborhood until around 5:30, I’m guessing, since I have no watch piece. A predawn light softens the night sky and there is more traffic on the streets as the city wakes from its slumber. A fire alarm punctuates the drone of cars with a steady, pulsing blare. The bodies around me stir. One by one we rise, then fold and stuff bedding into backpacks. Although my hips and shoulders feel a little sore, the rest of my body seems surprisingly refreshed. A few of us gather the cardboard and tote it to a recycling bin in the alley. No sign of our presence remains as we walk silently, as a group, toward Saint Francis House, where we anticipate coffee and breakfast. The blare of the fire alarm gradually fades. Day 2 of the street retreat has begun.